For many avid exercisers, delayed onset muscle soreness, or DOMS, is used as an indicator of a successful workout; however, for those unfamiliar with its symptoms or who have an underlying injury or pain condition, DOMS can be a discouraging, unpleasant, and sometimes frightening experience. DOMS is defined as muscle pain, stiffness, swelling, and weakness beginning 12-24 hours after a workout, peaking around 48 hours, and persisting up to 7 days. It is typically a subclinical condition, meaning most cases resolve without the need for medical intervention. Most people have experienced such soreness at some point in their lives — whether due to starting a new exercise routine or from pulling weeds in the garden on the first day of spring. My goal is to demystify* DOMS and provide tips on reducing your chances of having your fitness or rehabilitation goals derailed by this temporary condition. By the end, you’ll feel confident to march on with exercise despite the soreness!

*Spoiler alert: there is currently no scientific consensus on the specific cause of DOMS.

Break Down to Build Up

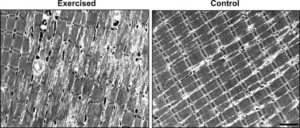

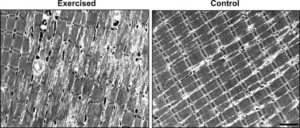

To provide some context for the discussion that follows, it will be helpful to take you through an abbreviated journey (think: The Magic School Bus) from the moment you perform an exercise, such as a biceps curl, through the first few days of recovery. When you lift a heavy weight for the first time in a while, you inflict exercise-induced damage, also known as microtrauma, to the muscle tissue. While this may sound scary it is a normal, typically healthy form of “injury” that leads to desirable adaptations including increases in muscle strength and size. (Curiously, the extent of microtrauma does not seem to correlate to the severity of DOMS1.)

In the hours/days that follow, like an episode of Extreme Makeover: Muscle Edition, your body gets to work not only repairing the affected tissue but making improvements to ensure that the next time you work out you’re prepared for the challenge. It accomplishes this through the action of immune cells, inflammatory enzymes, and genetic activity. The nerves and blood vessels that supply the muscle also become more active, increasing strength and power in as few as 1-2 weeks. Within 6-8 weeks of repeated exercise, visible changes such as increased muscle mass (AKA hypertrophy) become evident.

Getting Back to DOMS

Now let’s zoom back in to what’s going on the first 2-3 days following your biceps curl when you’re so sore that brushing your teeth is a struggle. I’d like to reiterate here that researchers are not in full agreement about the mechanism of DOMS. However, it’s still worth discussing a few of the more plausible hypotheses.

(Debunked) Theory #1: Soreness is the result of accumulated lactic acid in the exercised muscle. This is a popular one but is not accurate. While lactic acid plays a role in the burning sensation that occurs while you are lifting weights, it is not directly involved with the development of DOMS.

Theory #2: The aforementioned muscular microtrauma results in inflammation, sensitizing nerve endings and leading to pain. While this seems plausible, several studies have shown that the level of inflammation actually increases following subsequent workouts despite decreased levels of microtrauma and soreness2. It’s worth pointing out that while inflammation often gets a bad rap, it’s an essential part of recovery — it’s your body’s modus operandi for healing tissue and adapting to life’s stresses. Certain elements of the inflammatory process may be involved with DOMS, but inflammation alone does not seem to be an adequate explanation.

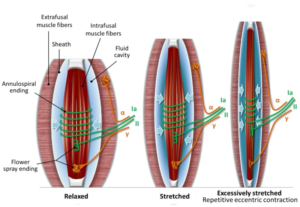

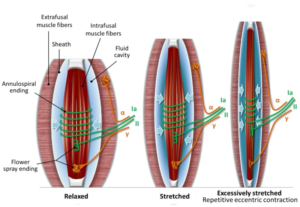

Theory #3: Physical and metabolic stresses during exercise cause microtrauma to the nerves that attach to the involved muscle fibers, which are then sensitized by a number of molecules spurred into action by the repair/rebuild process. This theory is hot off the press, having been published shortly before this post (September 2020)3. The idea is that, following exercise, nerves (depicted by the green and orange lines in the image below) are traumatized in a manner similar to muscles. Then, increased levels of nerve growth factor (NGF) and other restorative compounds sensitize the injured nerve endings. These compounds are distinct from inflammation, distinguishing this theory from the one above.

Theory #2 and #3 both have merit and the truth may be a combination of these factors. Nerve growth factor has been experimentally validated as a sensitizer of nerve endings and is produced in response to exercise, so this is likely to be a factor in DOMS. However, the extent to which muscle or nerve microtrauma and inflammation are involved is unclear.

If at first you’re sore, try, try again

Even though we don’t know exactly why DOMS happens, we do know that it’s a temporary condition as part of your body’s adaptive process. By executing these steps to recovery like a well-trained military unit, your body is able to adapt to new loads with remarkable efficiency. Within 1 week, a protective buffer allows you to repeat bouts of exercise with decreased soreness. This shield of DOMS protection can last as long as 4-12 weeks post-exercise and is referred to as the repeated bout effect4. The repeated bout effect is dose-dependent, meaning the greater the intensity or duration your first time exercising, the more protection you have for future efforts. However, even low loads (as few as 2 repetitions) can reduce the risk of DOMS the next time you work out. This should be encouraging to those who may be reluctant to start or continue exercising due to DOMS.

Can I work out when sore?

Yes. Exercising a sore muscle in moderation is not harmful to the muscle tissue nor the recovery process, though you may find you’re unable to exert as much force due to the strength deficits that accompany DOMS. Aerobic exercise is totally safe and will often help reduce the intensity of soreness in the affected areas5. While there is not much evidence to say that you shouldn’t work out a sore muscle, if you’re experiencing undue pain or fatigue while doing so it may be best to target another muscle group.

Chasing soreness

While the very first workout for an untrained individual is likely to result in DOMS, the repeated bout effect protects from perpetual soreness, and individual factors such as genetics also impact one’s susceptibility6. Furthermore, certain muscle groups are more likely to experience soreness than others. The fact is there isn’t much evidence that soreness is necessary for increasing strength or building muscle7. On the contrary, there is convincing evidence that strength and size can increase without muscle soreness8. So you don’t have to go searching for soreness to make gains.

Isn’t there a magic pill I can take?

Much time, effort, and money has been spent to reduce the incidence and severity of DOMS. However, many of these remedies have been deemed ineffective by science. For instance, stretching before and/or after exercise does not prevent DOMS9. Nor does massage10, ice11, Epsom salt12, or bee venom13 (yes, that’s a real study). This doesn’t mean that a good massage, stretch, ice bath, hot pack, (…or bee sting?) won’t curb symptoms once they set in. They just won’t reduce your chances of getting DOMS in the first place or decrease the duration of your misery.

If you really can’t stand DOMS, there are a few strategies to try. Some research has found that omega-3 fatty acid, caffeine, and taurine intake can potentially reduce symptom severity14 (disclaimer: discuss dietary supplementation with a medical provider). Light to moderate aerobic exercise such as riding a bike or jogging may help reduce DOMS when used as part of a warm up routine15. However, the best solution may be the most obvious: ease your way in. A 1- to 2-week preparatory exercise phase using lower volume and intensity reduces the soreness experienced with subsequent sessions16.

If you try all of the above and still get a case of the DOMS, do not fear. Father Time will take care of the soreness and your body will ensure that the next time you work out, the pain won’t be quite so bad. Trusting in your ability to repair and adapt will allow you to reap the numerous benefits that exercise has to offer.

Written by: Dr. Scott Newberry