If you’ve ever been to a physical therapist, you know that exercise is usually prescribed as the primary treatment for a number of injuries and conditions. Clearly exercise has numerous benefits, but it can sometimes seem counterintuitive to place resistance or load through an injured area — doesn’t it need time to rest and heal? The short answer to that question is generally yes, especially immediately following the injury; however, the right amount of movement and exercise can actually promote healing and recovery from injury. This is where PT comes in.

My goal is to help you understand just how exercise helps restore normal functioning of injured body tissues. This article is part of a series that will discuss how various types of tissue depend on movement to recover. Today’s subject is injured tendons and ligaments.

Tendon and ligament injuries range in terms of type and severity and are broadly categorized as tendinopathies or ruptures in the case of tendons and sprains in the case of ligaments. Examples of tendinopathy include tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow, and Achilles tendinopathy. You may have also heard the term “tendinitis” used with these conditions. Though complex and multifactorial in nature, tendinopathies often involve tissues that have become weakened and painful through repetitive usage. Ligament injuries are usually due to trauma — you’ve likely heard of athletes injuring their anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL.

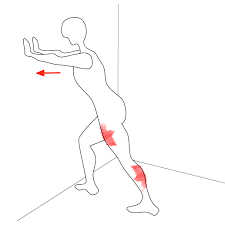

Tendons connect muscle to bone, transferring the force produced by a muscle into a nearby bone to create movement. Tendinopathies often develop in situations where a person puts a repetitive load through a tendon over a sustained period of time. It is most likely to occur when the level of activity is increased relative to baseline (i.e., too much too soon), such as someone taking up tennis for the first time in a while or playing more matches than usual.

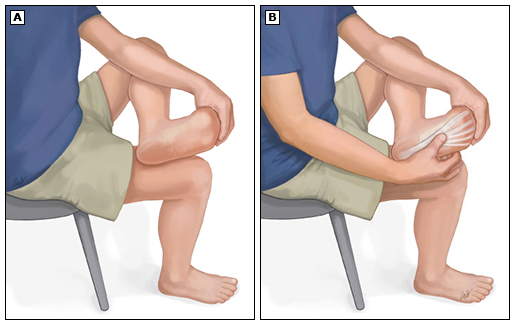

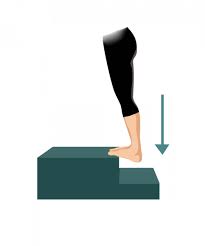

The sustained tendon stresses can cause areas in the tendon to become disarrayed and no longer align with the direction of applied force. In other words, the fibers aren’t able to convert muscle energy into movement as efficiently. The gold standard strategy to disrupt this process is to load the tendon through slow, heavy resistance training which stimulates the tendon to remodel itself and repair the injured areas. Eventually, the tendon becomes strong enough to handle loading without pain.

Ligaments connect one bone to another, protecting joints from moving in directions they shouldn’t. While ligaments are not exactly the same as tendons, the loading principles discussed with tendons allow them to handle higher loads through similar mechanisms — by increasing their thickness and the amount of force they can handle.

One very important thing to keep in mind is that immobilization is very detrimental to the strength and health of tendons and ligaments. Therefore, seeing a PT after injury may give you the best shot at retaining as much function as possible in the injured tissues.

Look out for the next article in the series about bones.

Written by: Dr. Scott Newberry